1.Introduction

Decisions in public health policy are supposed to follow rational epidemiological

considerations. Transmission risks, incidence and mortality rates should

guide the funding of control programs. In reality, though, risk acceptability,

social impact, and the needs of each risk group are subject to negotiation.

Even the seriousness of the health threat,

its epidemiological extension and dynamics, and the degree of knowledge

available are ambiguous. All are negotiated before being established and

used to argue for federal funds for scientific and medical research and

prevention.

Scientists arrive at the negotiating table

with proposals for making advances in control or cure of a disease. Public

health institutions come with proposals for prevention and educational

projects. On the "client" side of the table sit not only "the

State" (or government) but also organized at-risk and patient/survivor

groups. AIDS patients and male homosexual groups advocate more money for

AIDS research and prevention; women argue for funding for female reproductive

health; Aspartame victims lobby against its manufacturer and FDA policy....

And so on.

Pressure group strength and action is decisive

for the negotiations' outcomes and consequently for the success of funding

campaigns. At a time when medical research is pouring dozens of new treatments

into clinical trials, funding is visibly related to the victims' chances

of survival.

We analyze the case of Prostate Cancer (PCa)

and compare it to Breast Cancer (BCa) and AIDS. Prostate Cancer survivors

and their families (the "victims") are at a disadvantage in health policy

decisions. Funding for PCa research and prevention is much less than for

BCa or AIDS. This preferential allocation of public resources does not

correlate with either incidence or mortality. Mortality levels of PCa

and BCa are similar, while incidence is much higher for PCa. Both are

greater than AIDS. Relative amount of public money spent is not related

to epidemiological control: PCa incidence and mortality are rising, while

BCa's are decreasing.

The key to understanding these discrepancies

is organization  how effectively pressure groups are able to generate

political consensus about the relevance of their cause. What counts is

the coining of a politically correct problem.

Prostate,

PCa,

& Diagnosis

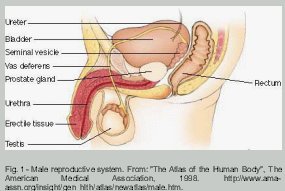

Click to view full size. Image file will open in a separate window, which can be stored on your task bar. Or click the next figure number to open the file again. Footnote numbers between slashes // link to another file in its own window. |

Cancer of the prostate is a male disease. The prostate is a muscular-glandular

organ situated at the base of the penis and under the bladder. The prostate

is responsible for the production of semen. Prostate problems increase

with age. Older men often experience enlargement of the organ, are more

prone to developing prostatitis, benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH), and/or

prostate cancer/1/.

Prostate tissue produces a specific protein

that is found both bound to cell membrane and in soluble form in the plasma.

It is called Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA). PSA testing became widespread

in the eighties/2/.

This tissue marker is used for the purpose of monitoring prostate health

and cancer development. Since PSA tests became a routine procedure, the

number of diagnosed PCa patients has increased /3/.

As most cancers do, PCa varies in aggressiveness

as well as with respect to pathological features of the cells. Pathologists

have developed a system of classification for cancer tissue with a scale

from 1 to 5 that measures loss of cell differentiation. Cancer cells lose

their original tissue identity; and evidence has shown that the further

they stray from the original, differentiated, pattern the more aggressive

their growth. On this scale, called "Gleason score" (named after the man

who formulated it) 1 is the closest to the normal structure of prostate

tissue and 5 is the most undifferentiated, or formless.

Pathologists examine pieces of prostate

tissue obtained by biopsy or during surgery. They look for the two commonest

tissue types, and define them with two Gleason scores. Each cancer patient

has an n + n Gleason score, 1 + 1 being the best and 5 + 5 being the worst

result/4/.

Treatment

Choices

What follows diagnosis is treatment choice/5/.

Usually this is the most difficult moment for the patient/6/.

He feels a sudden estrangement, as if something had set him apart from

the rest of the world. Loneliness and helplessness are made more intense

by the complexity of the controversies over treatment strategies.

Different specialists or even "schools"

favor different approaches to treatment. Most doctors will not recommend

the more aggressive procedures, such as Radical Prostatectomy, for men

over seventy. When the man is younger and the cancer appears not to have

spread beyond the prostate, options include Radiation Treatment (RT),

Cryosurgery, Radical Prostatectomy (RrP) and Watchful Waiting. They all

have serious downsides. RT might not be as effective as RrP. RrP is the

most aggressive intervention and results in impotence in 24% to 62% of

cases and incontinence in 5% to 19% /7/.

Watchful Waiting, a nice way of describing doing nothing about it, has

obvious downsides.

Advanced Disease

If diagnostic indicators show that the cancer is no longer contained in

the organ (it has become "systemic"), most doctors will not recommend

prostatectomy, but rather a combination of hormone and other treatments.

Hormone treatment is also called "chemical castration" because what it

actually does is neutralize male hormones, either by blocking their production

or by blocking receptors. Another option is orchiectomy, surgical removal

of the testicles (castration proper).

Castrated patients experience loss of libido,

metabolic problems and a range of symptoms that resemble menopause. Castration

is viewed as necessary because PCa cells are known to depend on androgens

for their growth; hormone deprivation dramatically halts cancer development

in most cases. However, the patient's cancer cells become "refractory"

in a period that might vary from one to ten years  cancer begins to grow

again despite hormone deprivation.

At this stage, it is very difficult to control

prostate cancer. Metastasis will preferentially spread to the bones and

the victim suffers great pain. Treatment is reduced to painkillers and

sedatives.

New experimental treatments, clinical trials

and nutritional research are very encouraging. However, today, the prospects

faced by the newly diagnosed patient are gruesome.

Impact

on Men's Sexuality

Besides the painful death, the most shocking effects of PCa for men are

those affecting their masculinity: impotence as a consequence of RrP,

incontinence, and the loss of libido that results from chemical or surgical

castration. PCa is seen as a disease that threatens and kills the man

inside them, the core of their identity.

Coping with such mutilating consequences

is made more difficult by prejudice and ignorance. Discussion about male

sexuality is rare in the press. Men and their families are not prepared

to deal with these facts. The small proportion of articles or TV programs

about men's sexuality is dominated by behavioral preferences of healthy

young males. Impotence is rarely approached and, when it is, is insufficiently

informative.

If healthy male sexual life is inadeqautely

discussed, the sexuality of men living with the impact of cancer and treatment

is utterly unknown. Available literature claims that, provided an artificial

erection device is employed, orgasm is "normal" in prostatectomized patients

and impotent men in general. However, the experience of survivors suggests

otherwise/8/

. A recent debate about sex after RrP in a survivor-to-physician electronic

discussion group has shown that most prostatectomized patients have a

variety of different sensations and experiences in their sexual lives.

It has also shown that most of these phenomena cannot be adequately explained

with the available knowledge. Doctors have generally had less to say about

the subject than participating survivors.

Prejudice and secrecy surround male orgasm,

impotence and incontinence. Despite the Kinsey Report decades ago, neither

the medical and scientific community nor the press have shown much interest

on these topics. PCa survivors may feel helpless in face of poverty of

available options. They may not know how to cope with these outcomes.

Old age aggravates prejudice. PCa is typically

an old age disease: Eighty percent of men found to have PCa are 65 and

over. Old people are not entitled to a regular sexual life in our society.

Thus, the issue of the sexual losses resulting from PCa treatment is dismissed.

2.Epidemiological

Data and Comparisons

PCa is the second most common cancer killer among men. The three most

important cancers for men, lung, prostate and colorectal, are depicted

in fig. 2.

PCa's incidence increases more than the other cancers' according to age.

Moreover, PCa seems to be rising in comparison to other cancers, as shown

by the numbers of new diagnoses (fig.

3). A closer comparison with breast cancer suggests that while the

latter shows a tendency towards control, PCa incidence is increasing (fig.

4).

The mounting numbers of PCa incidence partly

reflect the widespread use of PSA testing after the eighties. However,

the unchallenged rising mortality curve indicates the lack or failure

of control programs. The stabilization of the incidence curve for BCa

might reflect the opposite. Mortality is not as influenced by diagnosis

technology: BCa mortality is decreasing while PCa mortality is rising

(fig. 5).

When these curves are broken down by race

(fig. 6), trends

become sharper: PCa mortality is increasing both for white and black men,

but since the early 1970s, black men's rates have remained twice as high

as for white men. The rise is steeper for black men. BCa trends too differ

by race: in the early seventies mortality rates for white and black women

were similar. Mortality for white women stabilized and by the ninetiess

began falling. Black female mortality kept on rising steadily from the

late seventies on, peaking in the early nineties. It has been stable since.

The coincidence of rates of breast cancer

in the early seventies for black and white women suggests that genetics

or other biological conditions are not relevant explanations for the current

greater mortality among black women. Such a factor is frequently mentioned

in the case of PCa/9/.

Age differences between PCa and BCa incidence

give rise to value judgments in public debate. Both incidence and mortality

(fig. 7 and 8)

start earlier for BCa. Before the age of 60, BCa affects and kills more

women than PCa does men. Beyond that age, PCa continues to rise, with

a steeper slope than BCa. Claims based on age differences for incidence

and mortality tacitly suggest that women in their thirties and forties

are more relevant citizens than men in their fifties.

3.Organization:

The Force of Women

Women may be under-represented among decision-makers, but they are definitely

more organized than men. There are hundreds of Breast Cancer organizations

throughout the United States and they are connected. The National Alliance

of Breast Cancer Organizations, NABCO, established in 1986, today has

more than 370 member organizations. It has been involved in many advocacy

and educational activities.

In 1992, NABCO launched an education and

screening mammography program in partnership with the Liz Claiborne Foundation

to provide care to underserved women. In 1993, Avon's Breast Cancer Awareness

Crusade, a national education campaign, was started. NABCO was one of

the partners. That same year The Avon Breast Health Access Fund was established

and NABCO distributed $1.8 million to nearly 100 community education and

screening programs. In October 1994, NABCO and PolyGram Records released

Women for Women to benefit breast health awareness. NABCO is politically

very active: it serves on the Executive Committee of Secretary Donna Shalala's

National Action Plan on Breast Cancer, it had representatives on the Consensus

Development Panel of the June 1990 National Institutes of Health Conference

on Treatment of Early-Stage Breast Cancer and it testified before the

President's Cancer Panel.

NABCO was a primary organizer of the National

Breast Cancer Coalition (NBCC), a national advocacy organization established

in 1991. NBCC involves today more than 400 American organizations. Since

its beginnings, a more than fivefold increase in breast cancer appropriations

was observed. In the year it was founded, the NBCC set out the "Do the

Write Thing" letter campaign to deliver 175,000 letters to Congress and

the President  one letter for each projected breast cancer diagnosis

that year. It succeeded in delivering more than 600,000 letters.

In the following fiscal year, $132 million

was put into breast cancer research through the National Cancer Institute

(NCI), a gain of almost 50% over 1991 spending. In February 1992, NBCC

set up Research Hearings in Washington, DC, at which prominent scientists

testified. During Mother's Day weekend of 1992, NBCC coordinated 38 events

in 31 states. In July 1992, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) reauthorization

bill, which included $300 million for breast cancer, passed the House

and Senate, but was vetoed by President Bush. NBCC organized a powerful

reaction and their demands were finally met: more than $400 million was

assigned for breast cancer research: $210 million in the Department of

the Army and $200 million to the National Cancer Institute.

NBCC has campaigned for several Acts and

Resolutions since 1992. They met with Hillary Clinton during the presidential

campaign to brief her on breast cancer issues. NBCC representatives appeared

in several TV shows and held press conferences.

In 1993, NBCC launched a Campaign to send

2.6 million letters, postcards, signatures, faxes and mailgrams to President

Clinton asking for the development of a national strategy to end the epidemic.

President Clinton responded promptly: on December 14, 1993. Coalition

members, other breast cancer advocates and members of Congress, the Administration,

the scientific community, private industry and the media came together

to begin sharing ideas and discussing the elements of a strategy to end

breast cancer. NBCC members have assumed leadership positions in the ongoing

National Action Plan on Breast Cancer.

In 1995, NBCC developed Project LEAD, a

program for breast cancer activists to educate advocates in basic scientific

and medical language and concepts and in the structure of breast cancer

research decision-making. Project LEAD graduates seek out and participate

on research boards and committees.

Each year, NBCC sponsors an Annual Advocacy

Training Conference at which hundreds of breast cancer activists from

across the country are trained in advocacy skills and educated in the

legislative and research decision making processes. NBCC's Congressional

Forum Series informs and educates policy makers through briefings on specific

breast cancer policy issues. Each forum includes a scientist, a policy

analyst and a consumer.

In May 1996, NBCC launched its third national

petition to the President and Congress, aiming at 2.6 million signatures

in support of $2.6 billion in breast cancer research funding by the Year

2000. NBCCF collected nearly 2.7 by May 1997. NBCC launched a Voter Registration/Voter

Pledge Drive, facilitating registration for their members and asking them

to pledge to vote and get others to do so. They devised a ten-point policy

platform and required all public officials and candidates for office to

endorse it.

NBCC's Clinical Trials Project trains members

to work in partnership with industry and the scientific community in order

to expedite the conduct of clinical trials. NBCC established an affiliated

Political Action Committee (PAC) in 1997. With the money raised through

this PAC, NBCC aims to increase its activity and influence in federal

and state policies and elections.

In September 1997 in New York City, NBCC

hosted its first Workshop for the Media: Understanding Breast Cancer Research

and Policy. This workshop was directed to members of the media who are

responsible for writing and reporting on breast cancer. Federal appropriations

for breast cancer research this year exceed $500 million. The NBCC advocacy

model attracted international attention and established a paradigm for

action. The National Breast Cancer Coalition Fund (NBCCF) hosted the First

World Conference On Breast Cancer Advocacy- Influencing Change, on March

13-16, 1997 in Brussels, Belgium. They brought together more than 250

breast cancer activists from 43 countries and six continents.

As they have stated, "Perhaps the most

important change NBCC has brought about is acceptance of the idea that

breast cancer survivors MUST have a say when policies are formed and research

funding decisions are made." /10/

In a little more than one decade, breast

cancers activists in the United States multiplied several times the federal

appropriations for BCa research and control, educated the Press and Congress,

and professionalized activism. Activists now have a solid technical background

that covers medical issues as well as politics. There are efficient strategies

to promote voting power and influence Congress.

The organizational model of BCa activism,

established in the United States, is being internationalized. Countries

that lacked tradition in pressure group politics are rapidly absorbing

the "American way" of getting their interests respected.

If one side of BCa activism is its entrepreneurial

and professional outlook, the other is its feminist commitment. Another

founder of the NBCC was the Feminist Majority Foundation. In the Feminist

Majority site, Eleanor Smeal urges women to "work together to secure our

fair share of research dollars." Feminists hold that women suffer a historical

disadvantage in health assistance. They were engaged in breast cancer

advocacy from the beginning as part of a general agenda towards special

health programs for women. They demand more attention to female reproductive

issues, which are seen as the roots of the physical oppression of women.

They led pioneering efforts in activism and advocacy in the field of health.

And it worked.

4.Organizing

Prostate Cancer Activism

Five years after NBCC and lacking the support of a national alliance of

organizations with hundreds of members, the National Prostate Cancer Coalition

(NPCC) was born. In July 20, 1996, a group of prostate cancer advocates

met at Las Colinas, Texas, for this purpose. The NPCC was set up with

the available patient advocacy groups, including: American Cancer Society/Man

to Man/Side by Side; American Foundation for Urologic Disease; The American

Prostate Society; CaP Cure; The Mathews Foundation; MENCANACT; National

Coalition for Prostate Cancer Patients; New England Prostate Cancer Network;

Patient Advocates for Advanced Cancer Treatments; The Prostate Cancer

Communications Resource; The Prostate Cancer Education Council; Real Men

Can Cook; Tampa Bay Men's Cancer Task Force; US TOO International.

The quantity, quality and level of PCa

activism is way below those of BCa. Its National Coalition is weak and

small compared to the BCa Coalition. Trying to follow paths established

by women, they launched a petition campaign in 1997. Even though it is

more modest, with a target of one million signatures, it hasn't been able

to make significant progress towards that goal/11/.

| Breast Cancer | Prostate Cancer |

| National Breast Cancer Coalition (NABCO) · founded in 1991 · set up by the National Alliance of Breast Cancer Organizations and feminist organizations |

National Prostate Cancer Coalition (NPCC) · founded in 1996 · set up by some advocacy and survivor support groups |

| Y-ME - the largest BCa support group - founded in 1978 | US-TOO - the largest PCa support group - founded in 1990 |

| The 2.6 million signature campaign · demanding 2.6 billion research dollars · launched in May 1996 · successful results in one year: 2.7 million signatures |

The 1 million signature campaign: · demanding $175 million for prostate cancer research in the 1999 Defense Department Appropriations bill · launched in 1997 · poor results up to now |

As pressure for answers and guidance has increased, a new list was established: p2p (Patient to Physician). This is a moderated list. Patients are required to post their message with a clinical digest at the end. That is their signature. Each patient becomes his clinical history. Gleason score and PSA levels become part of his identity, and this is how he will report to the group. "The Circle" is more concerned with the emotional challenges of coping with the disease and with mutual support for caregivers, not least those whose partners are catastrophically ill or dying.

|

Table

2 - Main Prostate Cancer mailing lists

|

|

| Lists | Purposes |

| PPML | Prostate Problems Mailing List - discusses general issues, broadcasts recent research advances and welcomes newly diagnosed patients |

| PCPal | Prostate Cancer Patients Activist List - discusses campaigns and advocacy issues |

| p2p | Patient to Physician - a moderated list to discuss diagnosis and treatment alternatives |

| The Circle | Offers emotional support for survivors and their families |

| Seedpods | Discussion list for survivors who have chosen Radiation Implant Treatment |

5.Funding and Research

How much money does research require? This is a question administrators and science policy experts have been trying to answer for years. In the case of medical research on diseases such as cancer and AIDS, the ultimate desired product is the cure or control of the disease. The fundamental knowledge for the development of treatment strategies that can actually lead to cure are, unlike in the recent past, available. What is needed now is money to develop these strategies, test them in clinical trial stages, and eventually prescribe them for patients.

One example is the "cancer vaccine" strategy, where the therapy attempts to elicit an immune response to tumor cells. The identification and cloning of tumor-specific antigens makes this a promising approach. Encouraging results have been obtained with melanoma patients, with tumor regression in 42% of patients/12/.

Powerful drugs that attack and inhibit metastasis are being developed and are planned for commercialization in the near future/13/. They too have been nicknamed "PCa vaccines", although they are not based on an immunological approach.

Immunological therapies proper are being developed elsewhere. Jenner Biotherapies of San Ramon, California, announced positive results in a Phase I clinical trial of their PCa vaccine, OncoVax-PTM. The vaccine consists of recombinant PSA and a proprietary adjuvant formulated into liposome formulation and emulsified in light mineral oil/14/.

Meanwhile, gene-based therapy has already reached the clinical trial stage. Investigators at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston are enrolling prostate cancer patients for treatment with a "suicide gene." The clinical researchers will inject the herpes simplex virus-thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) gene. After the gene has time to migrate into cancer cells, the patients will receive the anti-viral agent ganciclovir. This strategy has been effective in animals/15/.

Most of the federal dollars devoted to cancer research are located at two institutions: the National Cancer Institute, which controls most of the money, and the Department of Defense. In the PCa budget for 1997, roughly $74 million comes from the NCI. Defense accounts for another $45 million.

6. Slicing the Pie

The following table compares NCI spending in 1996 and 1997 for the four most common types of cancer in the United States:

|

Table

3 - National Cancer Institute Spending, by Cancer Type. 1996 and

1997

|

||

| 1996 Spending (actual, in millions) | 1997 Spending (estimated, in millions) | |

| Breast | $317.5 | $332.9 |

| Lung | $119.4 | $123.3 |

| Colorectal | $98.0 | $99.0 |

| Prostate | $71.1 | $74.0 |

| Source: CancerNet from the National Cancer Institute - 1997 | ||

With such a significant increase in the pie, the question remains as to how the slices will be cut. Table 3 [above] shows that BCa receives more funding than lung, colorectal and prostate cancer together. Obviously, funding priority is not decided on the basis of the number of deaths. Furthermore, together, lung and colorectal cancers kill more women than BCa does. Thus, funding priority is not decided on the basis of gender-specific (female) mortality either.

This means that cancer funds, however large, will be sliced according to the strength of each interest group at play. Experience from the recent past has shown that to collide with BCa lobbyists is too great a task for PCa advocates. The Public Forum for Prostate Cancer was held in San Diego from September 13 to 14, 1997. There, activists discussed resolution SB 273, which should devote $2 million for cancer research/17/. PCa survivors and their families advocated for PCa priority in funding, but the result was frustrating: the approved resolution established that the funds should contemplate gender specific cancers not previously supported in the past. The failure in their strategy is due to the force of the lobbyists for female cancers. In that same year, in the Senate budgetary deliberations of the State of Massachusetts, the $1 million PCa prevention fund was threatened with being reduced to $500 thousand, while BCa received $5 million for the same purpose/18/.

Within the larger category of medical research, funds also seem to be granted according to the strength of interested groups. AIDS research receives much more funding than the cancers, as seen in fig. 9.

AIDS research receives almost ten times as much as PCa research. While each PCa death corresponds to $2,631 in research funds, each BCa death is worth $9,700 and each AIDS death $72,000/19/.

7.Concluding Remarks

Two related policy issues are mingled here. The first is: who should have precedence in life-saving efforts? And the second is: how should public funding for research be spent?

Precedence on life-saving and health policies could follow different rationales. Policies based chiefly on equitability principles could favor people with longer life expectancies. This would mean focusing on children. The leading cause of death in the youngest age group (1-4 years) is "accidents and adverse effects." In 1995, this cause was responsible for 36% of all deaths for the age group. Congenital anomalies comes next with 11% and then malignant neoplasms, with 8% /20/. According to this principle, the bulk of NIH grants would go to programs for adverse effects and accidents. In actuality, this does not happen.

Another way to be equitable would be to concentrate on those who are more prone to get sick and die. In this case, policies would concentrate on older age groups, who die primarily of heart disease and cancers. Cancer is the number one killer in the 45-64 years age group, before being displaced by heart disease in the 65 and over group. Another rationale would be to put a high value on a return from social investments through conservation of mature productivity and prevention of negative impact of death on dependents both younger and older. This would favor the 45-64 age group, with its cancer killers. Finally, one last possible rationale is to minimize injustice where the risk group for a certain disease or cause of death coincides with a minority. Diseases or risks affecting blacks, hispanics, women, homosexuals, Indian-Americans and other minorities would be granted special attention.

How Research Aims Mesh With Health Policy

Research funding issues partially overlap with health policy issues. The first rationale adopted in science policy, known as the "linear" model for research funding, presumed that there is a chain of actions that leads from basic research to desirable technological or medical products to society.

This linear model, a rationalization of the Ivory Tower, emerged in the World War II years and guided the establishment of the National Science Foundation and the emphasis in military research. According to the linear model, scientists turn out to be useful if they are given freedom to pursue research problems far beyond (and protected from) distracting demands of society. The linear model was the first attempt to establish a systematic governmental policy for science and technology. It has been out of use for a long time.

It was replaced with a view of science as the driving force of development. Since the mid-sixties, the growing awareness that science and technology should be planned drove most governments to create special organizations, funding agencies and advisory boards. "Science for development" survived well until the mid eighties. The economic reality of commercial war, with its emphasis on technology, suggested that the main thrust of an effective science policy should be to stimulate industrial innovation. That is how science and technology could contribute to enhance a country's competitiveness.

Basic science enjoys today a fraction of the prestige and rank it enjoyed in the past. These transformations have followed changes in science and technology and their relations with society at large. Today, science is practiced in a diversity of institutional environments and is increasingly transdisciplinary in nature. It has growing importance in economy and industry. It is increasingly problem-focused and socially accountable, involving larger social groups in setting of goals and priorities. Science became a commodity, governments became brokers and the clients are increasingly diverse/21/.

With the empowerment of different social actors plus demands for increased accountability by funding decision-makers, negotiating the relevance of research became more politically complex. Each client advocates its own interests and "the common good" is forgotten.

In interest group politics there is no general rational principle for social policy. It is the age of political correctness, where relevance is permanently negotiated by interest groups. Relevance and worth depend on each group's ability to persuade public opinion. Diffuse political consensus is the name of the game. Women have been successful in this enterprise. They have organized and have convinced public opinion that their health problems were disregarded and that they were disadvantaged. They have demanded special attention, more funding, and institutional space on a par with their claims. They have developed professional methods of influencing congressmen, the media, and public institutions. Serving women's interests has became politically correct; denying their requests can be dangerously incorrect. Their political correctness is so consensual that their dominance and advantage in health policy is never disputed.

The old view about a pervasive male dominance in society is of no use to explain the advantages secured by women in health policies. Power is related to the ability to organize and gain public recognition. It is also related to the degree to which the group determines political consensus. Men have never been considered a group with special problems. They have never before organized towards common interests on health conditions. PCa initiatives are among the first ones along this line. In the domain of health policies, men, the disorganized majority, failed where women succeeded.

© 1999 MarÃlia Coutinho & Gláucio A. D. Soares

All Rights Reserved

March 7, 1999

prostate cancer survivor news

http://www.psa-rising.com

©1999